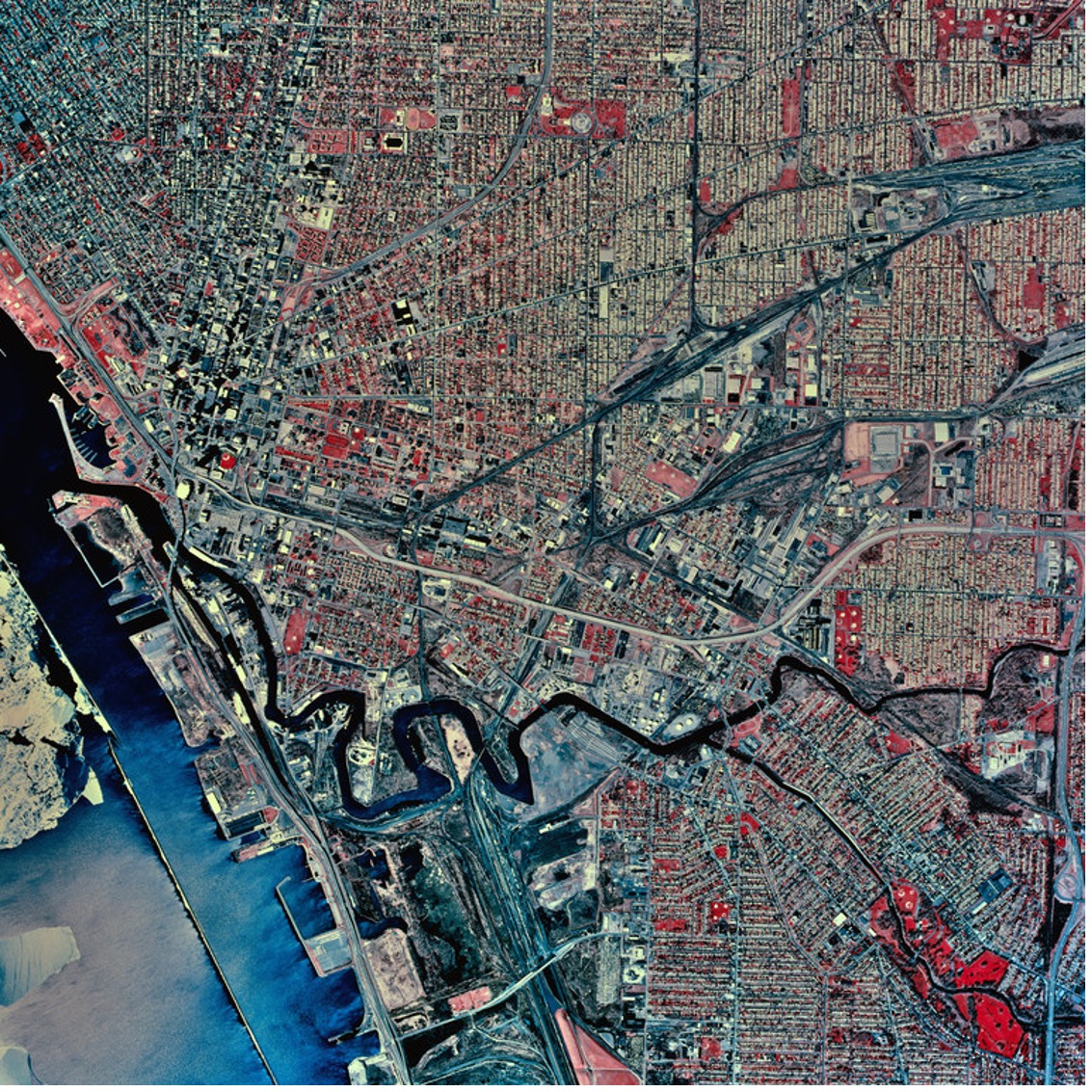

Historic Redlining Policies

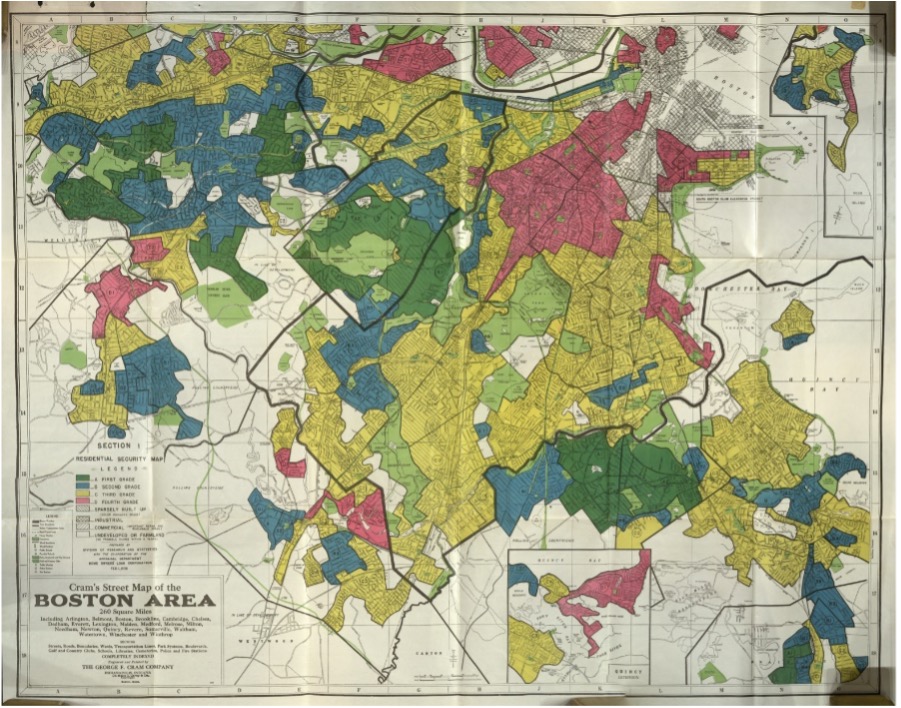

In the 1930s, the federal government created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) as part of an effort to standardize lending and make homeownership more accessible for many Americans. HOLC created “Residential Security” maps of 202 cities across the United States as part of its City Survey program. Neighborhoods were assigned grades according to their perceived mortgage lending risk. HOLC grades ranged from “A” to “D,” where A-graded areas (shaded in green) were considered “best” or safest for investment and D-graded areas were considered “hazardous” due to “detrimental influences in a pronounced degree, undesirable population or an infiltration of it.” The presence of people identifying as racial and ethnic minorities was very likely to result in being marked as a D-graded investment. Lenders were discouraged from making loans in D-graded areas, thereby promoting segregation and disinvestment in areas where people pertaining to racial and ethnic minorities groups lived.